Know Your Limitations

Kevin Ryan

Detection equipment training comes in many forms. The training can be formal in a conference session, or it may just be a technician taking a meter out of the box to refresh on it. My approach to training on detection equipment begins by asking one question. The question is this: Is your equipment smart or dumb? I get several puzzled looks once I pose this question. The answer lies in the eye of the beholder. The user may look at technology as an answer to help solve the mystery of a hazmat response. Another user may not trust newer technologies. The most brilliant answer I have ever gotten has been the equipment is only as smart as the user. The real answer lies in how well the user understands the limitations of the technology involved.

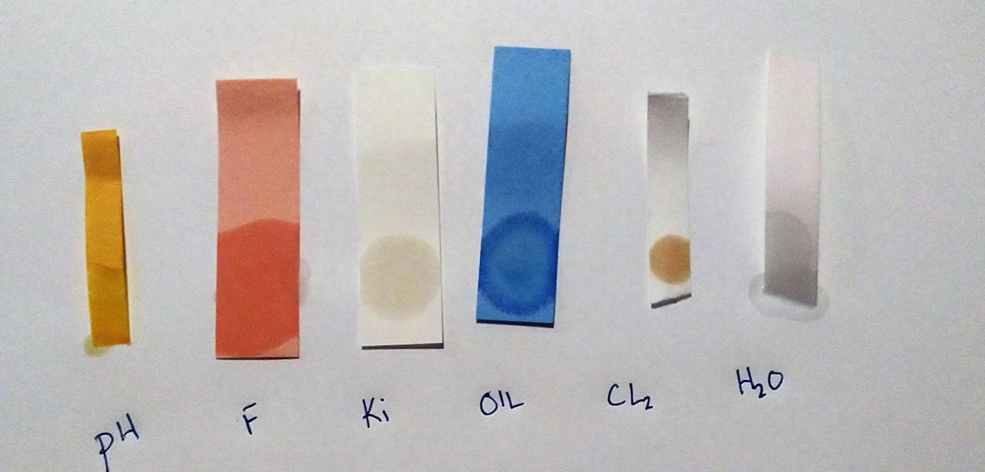

Let’s start with a simple piece of pH paper carried by every hazmat team. The piece of pH paper is really easy to interpret. Orange to red color change indicates acidic whereas green to blue shows a basic product. Some pH papers even read in different ranges and colors. Does the technician know what it means when there is a reading in the 4 to 8 range but presents in a straight line on the leading edge? What does it mean when the jagged edges are present in that same range of 4 to 8? Here I thought pH was the simplest of measurements and now it’s more complicated. The answer is that the straight line on the leading edge indicates the presence of a neutral substance possibly a hydrocarbon. The jagged edges indicate a likely corrosive. What happens if I check a liquid with pH paper that turns blue-green then a minute or so later whites out portions of the paper? The paper is “bleaching” out at that point indicating a strong oxidizer is present. The question that always comes up with pH paper is should I use it wet or dry? Multi range pH paper should be more than sensitive enough to use dry, however some teams will use it wet, to see if a water reactive is present.

Now you must be thinking to yourself that all of those possibilities are not shown on the packaging when you open the paper up. How many techs out there got this much information from their initial tech training? How many thought you could gain that much information from such a simple technology. How much more information can I gain when I use pH, water, F, KI, M9 together. Each one has their own set of limitations.

A multi gas meter is another example. Typical multi gas meters carry Cat B LEL sensors, toxicity sensors and possibly even a PID. Each sensor has a cross sensitivity, a correction factor or a characteristic that must be recognized when factoring into your reading. A Cat B LEL sensor can pick up all flammable gases besides the one you calibrate to necessitating correction factors. Toxicity sensors can have cross sensitivities as similar toxics can trigger readings. PID’s are nonspecific so you don’t have an idea of what specific chemical is present. The point I want to make here is that all detection equipment, no matter how advanced can be fooled, may not be sensitive enough, need correction factors and have a blind spot.

Advanced technologies such as IR, Raman, HP Mass Spec, IMS etc. are valuable in what they provide, however they bring on newer challenges such as interpretation. IR is fantastic however it does not see ionic bonds such as sodium chloride (ionic bonds are too strong to absorb IR energy). Optical technologies in general don’t see components of a mixture below 10 percent. We have found that IR typically only sees the cutting agents on street drugs and not the actual narcotic because of the 10 percent threshold. How do you keep up with all of this? The simple answer is never stop training. You can never train enough, especially with some of the newer technologies we are seeing in the hazmat world.

Training is the cure for all of our ills in the hazmat detection world. The training we receive should include all aspects of the equipment. What is it intended for? How does it work? What are the limitations of the device? Are there any uses out there for the device other than what it is intended for? Once you truly understand the limitations of the device, then you can be creative and use these to your advantage.

A good example of this is by using toxicity sensors cross sensitivities to your advantage. Hydrogen is a major cross sensitivity to a CO sensor. Although in most sensors the response of Hydrogen is approximately 20 percent of the CO reading, this is still a way to take a limitation and turn it in your favor. Most responders have gone to a CO response only to find out it was a battery powered forklift overcharging and giving off hydrogen. Your CO sensor was going crazy, and you could not figure out why there was not a fuel fired source present.

As with all things fire service oriented, storytelling is one of the most effective ways to pass on the lessons of our trade. We cannot learn everything in a book and need the real-world experience. Informal training through story telling can be very effective to prepare newer hazmat techs to become the senior tech that understands limitations we face on our responses. Never be afraid to ask yourself if there is more, I need to understand. Anyone that has ever been to a fitness club has heard the expression “train insane or remain the same”. Realistic training combined with real world experience is the key to understanding our equipment as well as our limitations.